SpyFi: Deep Learning for CSI-based Keylogging Side Channel Attacks

Introduction

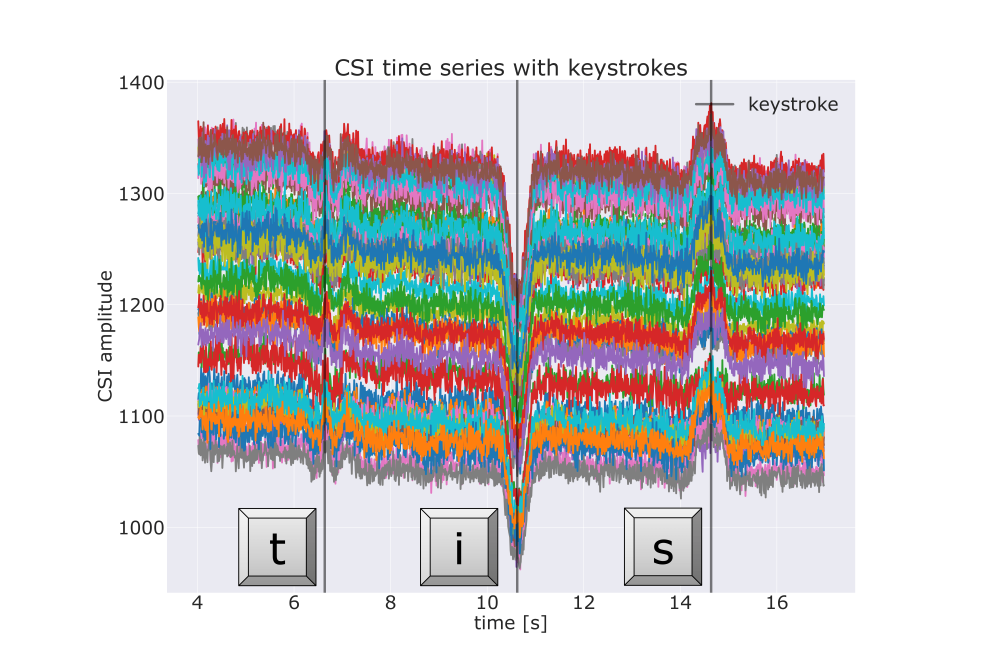

During keyboard typing, hand and finger movements induce alterations in Wi-Fi signal propagation, reflected in Channel State Information (CSI) values continuously monitored by Wi-Fi-enabled devices such as routers. Each keystroke's unique motion allows for the derivation of the typed key by correlating it with CSI time series patterns. The leaking of information about keystrokes from Wi-Fi signal distortions can be exploited posing a potential threat from side-channel keylogging attacks.

In our research, we implement and compare the conventional method found in related work to deep learning-based approaches to practically infer keystrokes from CSI time series. Motivated by the fact that the use of deep learning models promises less effort in pre-processing and feature extraction, we apply deep learning approaches for the first time for CSI-based keylogging and extend the knowledge about the applications of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Since keyboards serve as a ubiquitous means of interacting with computers, we address the security and privacy implications of these keylogging attacks. To empirically evaluate the performance of three implemented keyloggers we create a dataset worth more than 24 hours of recording time with a controlled experimental setup. Processing such a sizable dataset necessitates substantial computational resources, facilitated by access to the High-Performance Computing (HPC) infrastructure.

Methods

We derive an experimental setup that is used to capture CSI data during keyboard interaction. We conduct a pilot data study to generate a dataset surpassing 24 hours of recording time. The dataset includes variations for CSI influencing factors regarding typing behavior and experimental settings. Three keylogging approaches are implemented with Python including one classic machine learning approach and two DNN models called TSC ResNet11, and CRNN. The keylogging objective is divided into keystroke detection, discerning keystroke occurrences, and key identification, associating each keystroke with its corresponding pressed key.

Results

The machine learning models of the Classic, TSC ResNet11, and CRNN keyloggers are evaluated with cross-validation and standard performance metrics. The performance for the keystroke detection is calculated with regard to a temporal tolerance of 100 ms, which allows predictions to deviate slightly while still being counted as true positives. Leveraging our structured dataset, we assess keylogger performance across varying experimental factors. When evaluating the keystroke detection on data that originates from recordings that used a router distance of 0.65 m in the experimental setup, the best-performing model TSC ResNet11 achieves a mean balanced accuracy of 79.27%. A change in the router distance to 1.3 m leads to a decrease in performance to a balanced accuracy of only 71.70%. Similarly, we demonstrated the typing behavior to have an impact on the performance as well. Using fewer fingers for typing or a shorter router distance results in larger movement and, thus, easier detectable keystroke shapes in the CSI time series.

For the key identification, the DNNs show difficulties in learning from our dataset. The Classic keylogger that implements the k-nearest neighbors (kNN) classifier outperforms the DNNs with a mean top-3 accuracy of 22.17% considering 37 classes and a total of 3004 keystroke samples. Interestingly, a smaller room where CSI data is collected leads to higher accuracy in predicting keys. We explain it by the fact that the smaller the room is, the more multi-path effects occur, which leads to more unique features in the keystroke shapes of the CSI time series.

However, the top-performing models for keystroke detection and key identification entail significant computational costs. While TSC ResNet11 excels in keystroke detection, it also incurs the highest computational burden. Conversely, the Classic keylogger excels in key identification but scales quadratically with sample size, contrasting with the lower computational costs associated with DNNs.

Discussion

Our findings may not be directly comparable to other CSI-based keyloggers due to potential disparities in CSI extraction software, classic keylogging approach implementation, or CSI data quality. We observed significant quality degradation in CSI time series, characterized by abrupt fluctuations in CSI amplitude, possibly originating from Wi-Fi routers' Automatic Gain Control (AGC) functionality. Future investigations could implement more sophisticated pre-processing techniques to mitigate or rectify these effects. Moreover, the choice of CSI extraction software may impact the resulting data quality. Additionally, experimentation with DNN architectures or exploration of alternative models warrants consideration. The downsizing and reduction of parameters seems particularly promising to counter the potential overfitting of DNNs, representing a potential avenue for future research.